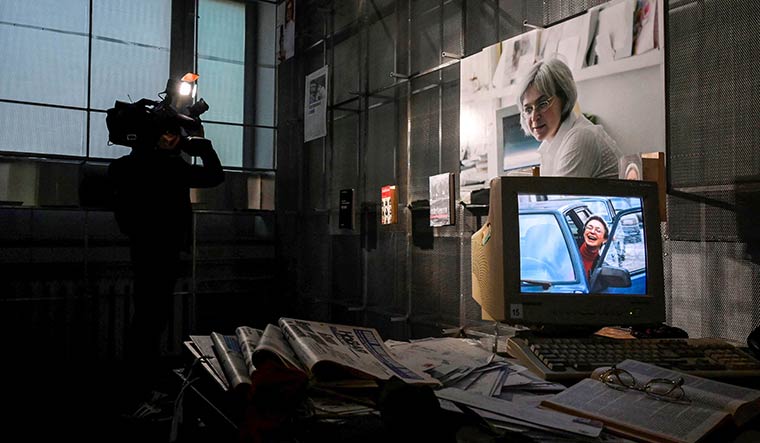

Q/ Six of your colleagues were murdered for their work. The Nobel Prize announcement came just a day after the 15th anniversary of your colleague Anna Politkovskaya’s assassination.

A/ The Nobel Prize is not awarded posthumously. I think that this prize should belong to those who risked their lives and were killed doing their jobs. Their life and death are the real fight for freedom of speech. I am not the beneficiary of this prize, but my outstanding colleagues are.

Q/ After Politkovskaya’s murder, you said you wanted to close down the Novaya Gazeta, and that no story was worth dying for.

A/ I did want to close down the newspaper, because I failed to protect my employees. I put Anna at risk, but this is a joint guilt. Yet, I am not the only one who runs the newspaper—we have an editorial board, which makes the decisions.

We argued a lot, we quarrelled, but nobody supported me. Our journalists said that we had no right to close down the newspaper. So, now we must conduct the investigation on our own and continue doing what Anna did—help people for whom the Novaya Gazeta is the last hope.

Q/ Do you remember the initial days of the Novaya Gazeta? What about the support you got from Mikhail Gorbachev and Aleksandr Lebedev?

A/ I met with Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev in 1989, when I was working at Komsomolskaya Pravda, the largest circulated newspaper in the Soviet Union. I had gone to interview him. Our friendship began there.

Gorbachev was the first shareholder of the Novaya Gazeta—he bought the first ten computers for us, as early as in 1993—spending a part of the money from his 1990 Nobel Prize. The first mobile phone was presented to our editorial office by his wife, Raisa Maksimovna Gorbachyova. I consider Gorbachev to be an outstanding person, politician and an advocate of peace.

Now, of course, I am proud that we have something in common [with the Nobel Prize]! At the editorial office, they joke that I am only the second one [with the prize]. Still, the Novaya Gazeta is the only periodical in the world with two Nobel Prize winners. We consider Gorbachev to be our friend, founder and shareholder. He holds 10 per cent of our shares.

As for Aleksandr Lebedev, we got to know each other in the early 2000s, when he was a deputy of the state Duma. Later, he became a businessman, and an oligarch. In 2006, he bought out 49 per cent of our shares (39 per cent on his own and 10 of Gorbachev; 51 per cent of the shares always belonged to the staff).

Lebedev literally saved us. Newspapers have never been a profitable business in Russia. We have always had problems with advertisers. In our country, advertisement is a political matter, but we have never taken money from the state, nor received any donations or grants. We were about to stop printing, when Lebedev stepped in.

He got more problems than profits. There were SWAT teams at his office, and they seized his documents. Eventually, four years ago, Lebedev returned 25 per cent of the shares to us. He never influenced the policy of the newspaper, and I will always be grateful to him for his support during those tough times.

Q/ Can you compare journalism in Russia under different political systems, from the communists to Putin?

A/ History is cyclical—everything repeats itself. The situation with the media now is very similar to what it was 40 years ago. There is censorship, new bans pop up all the time, the security system publishes new lists of what kind of information should not be gathered. But still there is an important difference. It is the internet era now—nothing can really be concealed. Even if you shut down the internet, information will seep through, anyway.

Q/ The Novaya Gazeta is one of the last independent media outlets in Russia, which has not been labelled as a “foreign agent”. Will accepting the Nobel Prize change that? Also, do you think Vladimir Putin has spared you so far, for some purpose? His chief spokesperson, Dmitri Peskov, in fact, congratulated you on winning the Nobel Prize.

A/ The very day we heard about the prize, we checked with the ministry of justice whether accepting it would constitute foreign financing. To be recognised as a foreign agent in Russia, you need to meet two conditions—political activity (they consider journalism to be political activity for some reason) and foreign money. They answered that the Nobel Prize was a special case, especially if the money would be spent for charity.

I don’t like the word “spared”. Nobody spared us. The ministry of justice puts you on the foreign agents’ register after checking the complaints. Eight such complaints were filed against us. This means that eight checks started at the same time, but they found no violations.

Several months ago, the building where our editorial office is located was targeted with a poisonous substance (not Novichok, but one just like that). Fortunately, there were no deaths. This attack happened at night, the substance got dissipated by morning, although the smell lasted for two more weeks.

We know who did this, but the culprits have not been found. Our correspondent in the Chechen capital, Grozny, was assaulted, but no culprits were found. And there are six dead, too. So, I cannot agree that someone spared us.

As for Peskov, I will not argue with him, he knows better!

Q/ There are critics who say that despite your strident criticism of the Putin regime, you are still prepared to engage with the Kremlin. You defended Aleksey Venediktov, the editor-in-chief of Ekho Moskvy, who supported the controversial online voting platform in the September elections. This, according to many critics, helped Putin’s United Russia party.

A/ Aleksey Venediktov is a close friend, a man of absolute honesty and iron-clad principles. The electronic voting system is perhaps imperfect and may require improvements, but I will always protect Venediktov from those who believe that he is playing into the hands of some people. They just don’t know him.

Q/ There are reports that you have friends among top politicians, senior law enforcement officers and even the oligarchs, which protects your brand of journalism. Is it the case of the end justifying the means?

A/ Most of those reports are untrue. I know lots of people, I have a few friends, but there is definitely no one among them who will help me survive. And I can say for sure that money does smell.

Q/ You said you would have given the Nobel Prize to jailed Kremlin critic Aleksey Navalny, had you been on the committee that decided the award.

A/ I may disagree with Aleksey Anatolyevich Navalny. We may argue, we may swear and even fight (this has not happened yet, but I am not excluding the possibility) over differing views and opinions, but only when he is free. When Navalny is in prison, I totally support him.

Q/ Across the world, the tendency to suppress the freedom of press seems to be growing, even in democratic countries.

A/ Power is too strong a drug. Many leaders, even democratic ones, cannot resist putting pressure on the media, once they come to power.

Q/ Although India is a democracy, it is ranked 142nd in the Reporters Without Borders Index on press freedom, just eight places above Russia.

A/ Unfortunately, I don’t know the realities of today’s India well enough. But going by the rating, I think the situation there is better than what it is here in Russia.

Q/ The other winner of the Nobel Peace Prize, Maria Ressa from the Philippines, is also an investigative journalist. Why do you think the Nobel committee has chosen two journalists for the prize?

A/ You better ask the committee. This tendency is ten years old now. Possibly, the committee sees much more in common between the nominees. I am very proud to share the prize with Maria Ressa. She is an outstanding journalist, and it is a great honour to have my name next to hers.

Q/ What do you think of the influence of social media on journalism?

A/ A professor who is a friend of mine put it like this: journalism is something you don’t want to know. And social media, with memes, trolls and pictures from vacations is something you want to know. This is why journalism has not gone anywhere after the bloggers came. The criteria have just become stricter. Journalism still requires fact-checking and opinions of all parties. Social media intensifies competition and makes the world more transparent.

Q/ What do you think of the future of independent journalism?

A/ The good thing about forecasts is that they do not come true. Who would have foretold the Covid-19 pandemic? And look how it has changed the world. As an editor-in-chief of a newspaper, I am confident of one thing: print newspapers will not disappear. But will there be anyone to read them? And will there be anything in them to read?